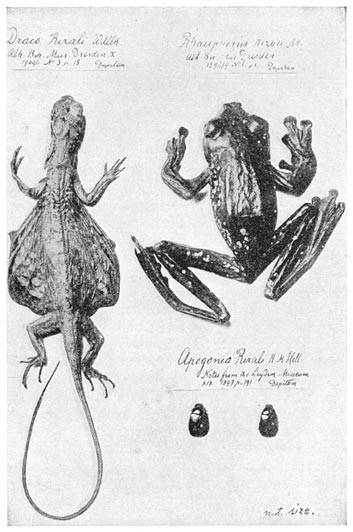

Three animal species were named after Rizal; Draco rizali, a species of flying dragon, Rachophorous rizali, a species of toad and Apogonia rizali, a beetle species.

Archive for the ‘Rizal’s Works’ Category

Discoveries.

Posted in Rizal's Life, Rizal's Works on November 7, 2012| Leave a Comment »

To the Filipino Youth

Posted in Rizal's Works on November 6, 2012| Leave a Comment »

“To the Filipino Youth”

(English version)

Unfold, oh timid flower

!Lift up your radiant brow,

This day, Youth of my native strand !

Your abounding talents show

Resplendently and grand,

Fair hope of my Motherland !

Soar high, oh genius great,

And with noble thoughts fill their mind;

The honor’s glorious seat,

May their virgin mind fly and find

More rapidly than the wind.

Descend with the pleasing light

Of the arts and sciences to the plain,

Oh Youth, and break forthright

The links of the heavy chain

That your poetic genius enchain.

See that in the ardent zone,

The Spaniard, where shadows stand,

Doth offer a shining crown,

With wise and merciful hand

To the son of this Indian land.

You, who heavenward rise

On wings of your rich fantasy,

Seek in the Olympian skies

The tenderest poesy,

More sweet than divine honey;

You of heavenly harmony,

On a calm unperturbed night,

Philomel’s match in melody,

That in varied symphony

Dissipate man’s sorrow’s blight;

You at th’ impulse of your mind

The hard rock animate

And your mind with great pow’r consigned

Transformed into immortal state

The pure mem’ry of genius great;

And you, who with magic brush

On canvas plain capture

The varied charm of Phoebus,

Loved by the divine Apelles,

And the mantle of Nature;

Run ! For genius’ sacred flame

Awaits the artist’s crowning

Spreading far and wide the fame

Throughout the sphere proclaiming

With trumpet the mortal’s name

Oh, joyful, joyful day,

The Almighty blessed be

Who, with loving eagerness

Sends you luck and happiness

From Chapter 7 of El Filibusterismo

Posted in Rizal's Works on November 6, 2012| Leave a Comment »

“Kayo, ano ang ginawa ninyo ukol sa bayang ito na kinakitaan ng unang liwanag, nagbigay-buhay sa inyo at nagdulot sa inyo ng ikatututo? Hindi ba ninyo alam na walang kabuluhan ang buhay na hindi iniuukol sa isang malayang layon? Iya’y isang munting batong natapon sa kaparangan na hindi kasama sa pagkabuo ng isang bahay.” — Dr. Jose Rizal, “Si Simoun” Chapter 7, El Filibusterismo

Novels

Posted in Rizal's Life, Rizal's Works on November 5, 2012| Leave a Comment »

During his stay in first stay in Europe, Rizal wrote his novel, Noli Me Tangere. The book was written in Spanish and first published in Berlin, Germany in 1887. The Noli, as it is more commonly known, tells the story of a young Filipino man who travels to Europe to study and returns home with new eyes to the injustices and corruption in his native land.

Rizal used elaborate characters to symbolize the different personalities and characteristics of both the oppressors and the oppressed, paying notable attention to Filipinos who had adopted the customs of their colonizers, forgetting their own nationality; the Spanish friars who were portrayed as lustful and greedy men in robes who sought only to satisfy their own needs, and the poor and ignorant members of society who knew no other life but that of one of abject poverty and cruelty under the yoke of the church and state. Rizal’s first novel was a scalding criticism of the Spanish colonial system in the country and Philippine society in general, was met with harsh reactions from the elite, the church and the government.

Upon his return to the country, he was summoned by the Governor General of the Philippine Islands to explain himself in light of accusations that he was a subversive and an inciter of rebellion. Rizal faced the charges and defended himself admirably, and although he was exonerated, his name would remain on the watch list of the colonial government. Similarly, his work also produced a great uproar in the Catholic Church in the country, so much so that later, he was excommunicated.

Despite the reaction to his first novel, Rizal wrote a second novel, El Filibusterismo, and published it in 1891. Where the protagonist of Noli, Ibarra, was a pacifist and advocate of peaceful means of reforms to enact the necessary change in the system, the lead character in Fili, Simeon, was more militant and preferred to incite an armed uprising to achieve the same end. Hence the government could not help but notice that instead of being merely a commentary on Philippine society, the second novel could become the catalyst which would encourage Filipinos to revolt against the Spanish colonizers and overthrow the colonial government.

Source: joserizal.com

Canto del Viajero

Posted in Rizal's Works, tagged hero, jose rizal, philippine national hero, poem on November 5, 2012| Leave a Comment »

“Dry leaf that flies at random

till it’s seized by a wind from above:

so lives on earth the wanderer,

without north, without soul, without country or love!

Anxious, he seeks joy everywhere

and joy eludes him and flees,

a vain shadow that mocks his yearning

and for which he sails the seas.

Impelled by a hand invisible,

he shall wander from a place;

memories shall keep him company –

of loved ones, of happier days.

A tomb perhaps in the desert,

a sweet refuge, he shall discover,

by his country and the world forgotten…

Rest quiet: the torment is over.

And they envy the hapless wanderer

as across the earth he persists!

Ah, they know not of the emptiness

in his soul, where no love exists.

The pilgrim shall return to his country,

shall return perhaps to his shore;

and shall find only ice and ruin,

perished loves, and graves – nothing more.

Begone, wanderer! In your own country

a stranger now and alone!

Let the other sing of loving, who are happy – but you, begone!

Begone, wanderer! Look not behind you

nor grieve as you leave again.

Begone, wanderer: stifle your sorrows!

The world laughs at another’s pain.”

Canto del Viajero by Jose Rizal

The Reign of Greed

Posted in Rizal's Works, tagged el filibusterismo, jose rizal, novel, the reign of greed on November 3, 2012| Leave a Comment »

The Reign of Greed or El Filibusterismo, Jose Rizal’s second novel.

Plot Summary

Thirteen years after leaving the Philippines, Crisostomo Ibarra returns as Simoun, a rich jeweler sporting a beard and blue-tinted glasses, and a confidant of the Captain-General. Abandoning his idealism, he becomes a cynical saboteur, seeking revenge against the Spanish Philippine system responsible for his misfortunes by plotting a revolution. Simoun insinuates himself into Manila high society and influences every decision of the Captain-General to mismanage the country’s affairs so that a revolution will break out. He cynically sides with the upper classes, encouraging them to commit abuses against the masses to encourage the latter to revolt against the oppressive Spanish colonial regime. This time, he does not attempt to fight the authorities through legal means, but through violent revolution using the masses. Simoun has reasons for instigating a revolution. First is to rescue María Clara from the convent and second, to get rid of ills and evils of Philippine society. His true identity is discovered by a now grown-up Basilio while visiting the grave of his mother, Sisa, as Simoun was digging near the grave site for his buried treasures. Simoun spares Basilio’s life and asks him to join in his planned revolution against the government, egging him on by bringing up the tragic misfortunes of the latter’s family. Basilio declines the offer as he still hopes that the country’s condition will improve.

Basilio, at this point, is a graduating student of medicine at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila. After the death of his mother, Sisa, and the disappearance of his younger brother, Crispín, Basilio heeded the advice of the dying boatman, Elías, and traveled to Manila to study. Basilio was adopted by Captain Tiago after María Clara entered the convent. With Captain Tiago’s help, Basilio was able to go to Colegio de San Juan de Letrán where, at first, he is frowned upon by his peers and teachers not only because of the color of his skin but also because of his shabby appearance. Captain Tiago’s confessor, Father Irene is making Captain Tiago’s health worse by giving him opium even as Basilio tries hard to prevent Captain Tiago from smoking it. He and other students want to establish a Spanish language academy so that they can learn to speak and write Spanish despite the opposition from the Dominican friars of the Universidad de Santo Tomás. With the help of a reluctant Father Irene as their mediator and Don Custodio’s decision, the academy is established; however they will only serve as caretakers of the school not as the teachers. Dejected and defeated, they hold a mock celebration at a pancitería while a spy for the friars witnesses the proceedings.

Simoun, for his part, keeps in close contact with the bandit group of Kabesang Tales, a former cabeza de barangay who suffered misfortunes at the hands of the friars. Once a farmer owning a prosperous sugarcane plantation and a cabeza de barangay (barangay head), he was forced to give everything to the greedy and unscrupulous Spanish friars. His son, Tano, who became a civil guard was captured by bandits; his daughter Julî had to work as a maid to get enough ransom money for his freedom; and his father, Tandang Selo, suffered a stroke and became mute. Before joining the bandits, Tales took Simoun’s revolver while Simoun was staying at his house for the night. As payment, Tales leaves a locket that once belonged to María Clara. To further strengthen the revolution, Simoun has Quiroga, a Chinese man hoping to be appointed consul to the Philippines, smuggle weapons into the country using Quiroga’s bazaar as a front. Simoun wishes to attack during a stage play with all of his enemies in attendance. He, however, abruptly aborts the attack when he learns from Basilio that María Clara had died earlier that day in the convent.

A few days after the mock celebration by the students, the people are agitated when disturbing posters are found displayed around the city. The authorities accuse the students present at the pancitería of agitation and disturbing peace and has them arrested. Basilio, although not present at the mock celebration, is also arrested. Captain Tiago dies after learning of the incident and as stated in his will—forged by Irene, all his possessions are given to the Church, leaving nothing for Basilio. Basilio is left in prison as the other students are released. A high official tries to intervene for the release of Basilio but the Captain-General, bearing grudges against the high official, coerces him to tender his resignation. Julî, Basilio’s girlfriend and the daughter of Kabesang Tales, tries to ask Father Camorra’s help upon the advice of an elder woman. Instead of helping Julî, however, the priest tries to rape her as he has long-hidden desires for Julî. Julî, rather than submit to the will of the friar, jumps over the balcony to her death. Basilio is soon released with the help of Simoun. Basilio, now a changed man, and after hearing about Julî’s suicide, finally joins Simoun’s revolution. Simoun then tells Basilio his plan at the wedding of Paulita Gómez and Juanito, Basilio’s hunch-backed classmate. His plan was to conceal an explosive which contains nitroglycerin inside a pomegranate-styled Kerosene lamp that Simoun will give to the newlyweds as a gift during the wedding reception. The reception will take place at the former home of the late Captain Tiago, which was now filled with explosives planted by Simoun. According to Simoun, the lamp will stay lighted for only 20 minutes before it flickers; if someone attempts to turn the wick, it will explode and kill everyone—important members of civil society and the Church hierarchy—inside the house. Basilio has a change of heart and attempts to warn Isagani, his friend and the former boyfriend of Paulita. Simoun leaves the reception early as planned and leaves a note behind:

“ Mene Thecel Phares. ”

—Juan Crisostomo Ibarra

Initially thinking that it was simply a bad joke, Father Salví recognizes the handwriting and confirms that it was indeed Ibarra’s. As people begin to panic, the lamp flickers. Father Irene tries to turn the wick up when Isagani, due to his undying love for Paulita, bursts in the room and throws the lamp into the river, sabotaging Simoun’s plans. He escapes by diving into the river as guards chase after him. He later regrets his impulsive action because he had contradicted his own belief that he loved his nation more than Paulita and that the explosion and revolution could have fulfilled his ideals for Filipino society.

Simoun, now unmasked as the perpetrator of the attempted arson and failed revolution, becomes a fugitive. Wounded and exhausted after he was shot by the pursuing Guardia Civil, he seeks shelter at the home of Father Florentino, Isagani’s uncle, and comes under the care of doctor Tiburcio de Espadaña, Doña Victorina’s husband, who was also hiding at the house. Simoun takes poison in order for him not to be captured alive. Before he dies, he reveals his real identity to Florentino while they exchange thoughts about the failure of his revolution and why God forsook him. Florentino opines that God did not forsake him and that his plans were not for the greater good but for personal gain. Simoun, finally accepting Florentino’s explanation, squeezes his hand and dies. Florentino then takes Simoun’s remaining jewels and throws them into the Pacific Ocean with the corals hoping that they would not be used by the greedy, and that when the time came that it would be used for the greater good, when the nation would be finally deserving liberty for themselves, the sea would reveal the treasures.

Source: Wikipedia

Touch Me Not

Posted in Rizal's Works, tagged jose rizal, noli me tangere, novel, touch me not on November 3, 2012| Leave a Comment »

Touch Me Not or Noli Me Tangere, was Jose Rizal’s first novel.

Reference for the novel

José Rizal, a Filipino nationalist and medical doctor, conceived the idea of writing a novel that would expose the ills of Philippine society after reading Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He preferred that the prospective novel express the way Filipino culture was backward, anti-progress, anti-intellectual, and not conducive to the ideals of the Age of Enlightenment. He was then a student of medicine in the Universidad Central de Madrid.

In a reunion of Filipinos at the house of his friend Pedro A. Paterno in Madrid on 2 January 1884, Rizal proposed the writing of a novel about the Philippines written by a group of Filipinos. His proposal was unanimously approved by the Filipinos present at the party, among whom were Pedro, Maximino and Antonio Paterno, Graciano López Jaena, Evaristo Aguirre, Eduardo de Lete, Julio Llorente and Valentin Ventura. However, this project did not materialize. The people who agreed to help Rizal with the novel did not write anything. Initially, the novel was planned to cover and describe all phases of Filipino life, but almost everybody wanted to write about women. Rizal even saw his companions spend more time gambling and flirting with Spanish women. Because of this, he pulled out of the plan of co-writing with others and decided to draft the novel alone.

Plot

Having completed his studies in Europe, young Juan Crisóstomo Ibarra y Magsalin comes back to the Philippines after a 7-year absence. In his honor, Don Santiago de los Santos “Captain Tiago,” a family friend, threw a get-together party, which was attended by friars and other prominent figures. One of the guests, former San Diego curate Fray Dámaso Vardolagas belittled and slandered Ibarra. Ibarra brushed off the insults and took no offense; he instead politely excused himself and left the party because of an allegedly important task.

The next day, Ibarra visits María Clara, his betrothed, the beautiful daughter of Captain Tiago and affluent resident of Binondo. Their long-standing love was clearly manifested in this meeting, and María Clara cannot help but reread the letters her sweetheart had written her before he went to Europe. Before Ibarra left for San Diego, Lieutenant Guevara, a Civil Guard, reveals to him the incidents preceding the death of his father, Don Rafael Ibarra, a rich hacendero of the town.

According to Guevara, Don Rafael was unjustly accused of being a heretic, in addition to being a subversive — an allegation brought forth by Dámaso because of Don Rafael’s non-participation in the Sacraments, such as Confession and Mass. Dámaso’s animosity against Ibarra’s father is aggravated by another incident when Don Rafael helped out on a fight between a tax collector and a child fighting, and the former’s death was blamed on him, although it was not deliberate. Suddenly, all of those who thought ill of him surfaced with additional complaints. He was imprisoned, and just when the matter was almost settled, he died of sickness in jail. Still not content with what he had done, Dámaso arranged for Don Rafael’s corpse to be dug up from the Catholic Church and brought to a Chinese cemetery, because he thought it inappropriate to allow a heretic a Catholic burial ground. Unfortunately, it was raining and because of the bothersome weight of the body, the undertakers decide to throw the corpse into a nearby lake.

Revenge was not in Ibarra’s plans, instead he carried through his father’s plan of putting up a school, since he believed that education would pave the way to his country’s progress (all over the novel the author refers to both Spain and the Philippines as two different countries as part of a same nation or family, with Spain seen as the mother and the Philippines as the daughter). During the inauguration of the school, Ibarra would have been killed in a sabotage had Elías — a mysterious man who had warned Ibarra earlier of a plot to assassinate him — not saved him. Instead the hired killer met an unfortunate incident and died. The sequence of events proved to be too traumatic for María Clara who got seriously ill but was luckily cured by the medicine Ibarra sent.

After the inauguration, Ibarra hosted a luncheon during which Dámaso, gate-crashing the luncheon, again insulted him. Ibarra ignored the priest’s insolence, but when the latter slandered the memory of his dead father, he was no longer able to restrain himself and lunged at Dámaso, prepared to stab him for his impudence. As a consequence, Dámaso excommunicated Ibarra, taking this opportunity to persuade the already-hesitant Tiago to forbid his daughter from marrying Ibarra. The friar wished María Clara to marry Linares, a Peninsular who had just arrived from Spain.

With the help of the Governor-General, Ibarra’s excommunication was nullified and the Archbishop decided to accept him as a member of the Church once again. But, as fate would have it, some incident of which Ibarra had known nothing about was blamed on him, and he is wrongly arrested and imprisoned. The accusation against him was then overruled because during the litigation that followed, nobody could testify that he was indeed involved. Unfortunately, his letter to María Clara somehow got into the hands of the jury and is manipulated such that it then became evidence against him by the parish priest, Fray Salví. With Machiavellian precision, Salví framed Ibarra and ruined his life just so he could stop him from marrying María Clara and making the latter his concubine.

Meanwhile, in Capitan Tiago’s residence, a party was being held to announce the upcoming wedding of María Clara and Linares. Ibarra, with the help of Elías, took this opportunity to escape from prison. Before leaving, Ibarra spoke to María Clara and accused her of betraying him, thinking that she gave the letter he wrote her to the jury. María Clara explained that she would never conspire against him, but that she was forced to surrender Ibarra’s letter to Father Salvi, in exchange for the letters written by her mother even before she, María Clara, was born. The letters were from her mother, Pía Alba, to Dámaso alluding to their unborn child; and that María Clara was therefore not Captain Tiago’s biological daughter, but Dámaso’s.

Afterwards, Ibarra and Elías fled by boat. Elías instructed Ibarra to lie down, covering him with grass to conceal his presence. As luck would have it, they were spotted by their enemies. Elías, thinking he could outsmart them, jumped into the water. The guards rained shots on him, all the while not knowing that they were aiming at the wrong man.

María Clara, thinking that Ibarra had been killed in the shooting incident, was greatly overcome with grief. Robbed of hope and severely disillusioned, she asked Dámaso to confine her into a nunnery. Dámaso reluctantly agreed when she threatened to take her own life, demanding, “the nunnery or death!” Unbeknownst to her, Ibarra was still alive and able to escape. It was Elías who had taken the shots.

It was Christmas Eve when Elías woke up in the forest fatally wounded, as it is here where he instructed Ibarra to meet him. Instead, Elías found the altar boy Basilio cradling his already-dead mother, Sisa. The latter lost her mind when she learned that her two sons, Crispín and Basilio, were chased out of the convent by the sacristan mayor on suspicions of stealing sacred objects. (The truth is that, it was the sacristan mayor who stole the objects and only pinned the blame on the two boys. The said sacristan mayor actually killed Crispín while interrogating him on the supposed location of the sacred objects. It was implied that the body was never found and the incident was covered-up by Salví).

Elías, convinced that he would die soon, instructs Basilio to build a funeral pyre and burn his and Sisa’s bodies to ashes. He tells Basilio that, if nobody reaches the place, he come back later on and dig for he will find gold. He also tells him (Basilio) to take the gold he finds and go to school. In his dying breath, he instructed Basilio to continue dreaming about freedom for his motherland with the words:

“ I shall die without seeing the dawn break upon my homeland. You, who shall see it, salute it! Do not forget those who have fallen during the night. ”

Elías died thereafter.

In the epilogue, it was explained that Tiago became addicted to opium and was seen to frequent the opium house in Binondo to satiate his addiction. María Clara became a nun where Salví, who has lusted after her from the beginning of the novel, regularly used her to fulfill his lust. One stormy evening, a beautiful crazy woman was seen at the top of the convent crying and cursing the heavens for the fate it has handed her. While the woman was never identified, it is insinuated that the said woman was María Clara.

Publication History

Rizal finished the novel in December 1886. At first, according to one of Rizal’s biographers, Rizal feared the novel might not be printed, and that it would remain unread. He was struggling with financial constraints at the time and thought it would be hard to pursue printing the novel. A financial aid came from a friend named Máximo Viola which helped him print his book at a fine print media in Berlin named Berliner Buchdruckerei-Aktiengesellschaft. Rizal at first, however, hesitated but Viola insisted and ended up lending Rizal P300 for 2,000 copies; Noli was eventually printed in Berlin, Germany. The printing was finished earlier than the estimated five months. Viola arrived in Berlin in December 1886, and by March 21, 1887, Rizal had sent a copy of the novel to his friend Blumentritt.

On August 21, 2007, a 480-page then-latest English version of Noli Me Tángere was released to major Australian book stores. The Australian edition of the novel was published by Penguin Books Classics, to represent the publication’s “commitment to publish the major literary classics of the world.”[4] American writer Harold Augenbraum, who first read the Noli in 1992, translated the novel. A writer well-acquainted with translating other Hispanophone literary works, Augenbraum proposed to translate the novel after being asked for his next assignment in the publishing company. Intrigued by the novel and knowing more about it, Penguin nixed their plan of adapting existing English versions and instead translated it on their own.

Source: Wikipedia